- When over 1,000 workers went on strike at the Yangzhou Baoyi Shoe Factory in Jiangsu province in late November 2023 over the factory’s closure, they pointed to the Taiwanese parent company Pou Chen and how it has been migrating its supply chain to Indonesia. Pou Chen supplies to brands including Nike, Adidas, Asics, New Balance, Timberland, and Salomon.

- Based on factory notices and workers’ online posts, China Labour Bulletin found that the Baoyi factory violated several provisions of China’s labour laws, including non-payment of social security and provident housing fund. Moreover, its enterprise union was absent during the strike, and the local branches of China’s official trade union said they were not aware of the strike, and one even denied that the strike occurred at all.

- In light of shifting supply chains and effects on workers across the region, China Labour Bulletin urges international brands, suppliers, and other stakeholders to take up their responsibilities to ensure global supply chains are fairly operated and that known violations of workers’ rights are remedied.

Over 1,000 workers at the Yangzhou Baoyi Shoe Factory (扬州宝亿制鞋有限公司) in Jiangsu province went on strike from 29 November to 7 December 2023 to demand a concrete calculation of the economic compensation guaranteed by law upon the factory’s shutdown.

Workers were aware that shoe orders were moving to Indonesia, and there was nothing they could do to keep the factory open. A worker posted a video of the strike on the short-video platform Douyin and confirmed their understanding of the supply chain changes in the comments:

By 1 January, all Converse orders will have gone to Indonesian factories.

The Baoyi shoe factory issued a notice on 29 November stating that the factory would close on 31 December and that employment contracts would also terminate that day. The notice specified that the precise basis for economic compensation would be revealed after 20 December. Dissatisfied with this uncertainty, workers went on strike.

Photograph: Pinar Alver / Shutterstock.com

Generally, the factory stated that workers’ economic compensation would be determined, according to the Labour Contract Law, by the average monthly wage for the 2023 calendar year times the number of years worked at Baoyi.

A commenter on a video about the strike posted on Douyin wrote:

This factory is so smart. [The closure] has been delayed for a year. This year, there is no overtime and the basic salary is low, so the compensation is much less.

Another online commenter suggested that workers would make off quite well with the severance package, but Baoyi workers disputed this:

A: You’ll be rich! Those who have worked for a long time can get hundreds of thousands of yuan in compensation.

B: You are thinking too much. The average salary is 3-4,000 yuan per month, so how do you work that out to hundreds of thousands? The factory was only established about 16 years ago.

C: Ordinary employees have an average salary of less than 3,400 yuan per month.

In fact, one worker, surnamed Jia, posted a blurry video of her compensation package that shows she is to receive 35,448 yuan (about U.S. $5,000) in economic compensation. Jia said she had worked at Baoyi for eight years and nine months, starting at the age of 25. As a production line operator, her monthly wage in the last year ranged from 3,200 to 4,700 yuan.

She signed a termination letter on 27 December 2023, and the 35,448 yuan she is owed reflects an average monthly wage of about 3,800 for each year of seniority rounded up to nine, plus one additional month of compensation, less about 2,600 yuan for her housing provident fund payment.

Many Baoyi workers are older or middle-aged women migrant workers, and some have worked at Baoyi for over a decade.

The strike was mainly to push the factory to clarify how workers’ economic compensation would be calculated. But some workers further alleged that their contract termination wholly violated China’s labour laws, as workers with over 15 years’ seniority are granted special protections. Therefore, some workers with long service argued they were owed double the economic compensation for the illegal contract termination.

Knowing their window for asserting their rights was closing, workers went on strike between 29 November and 7 December. A commenter warned workers that they could get arrested for striking, but workers shot back:

How do you know it’s useless?

In a video posted on 27 December, workers are seen leaving the premises for good. Some left comments about their positive memories working at Baoyi.

CLB investigation reveals that factory violated China’s labour laws and union failed to uphold workers’ rights

The day after the strike began, Baoyi issued a notice stating that the average monthly wage would be calculated according to the Labour Contract Law. However, this did not satisfy the workers, as their December 2023 wages were unknown, and they continued their strike.

On 1 December, workers were invited to negotiations with a government lawyer and representatives from several government departments. In a video posted by the workers, about a hundred workers are seen crowded around the lawyer, and workers said that the issue of compensation was not resolved after this conversation.

Baoyi workers attend a negotiation about their compensation plan. Source: CLB Strike Map (Douyin)

On 7 December, Baoyi issued a supplementary announcement, changing the calculation to use the average monthly wage from December 2022 to November 2023, plus they would give workers one additional month’s average salary. Workers were then able to calculate exactly how much economic compensation they would receive, and they resumed work that day.

However, this supplementary notice acknowledged the non-payment of workers’ social security and housing provident funds.

China Labour Bulletin made a call on 8 December to the human resources and social security bureau at the level of the Yangzhou Economic and Technological Development Zone, where the Baoyi factory is located. The Social Security Bureau staff told us that unpaid social security at Baoyi is “a historical problem” and that, although the authorities know about the violation, “there are always reasonable and legitimate reasons” for not enforcing the law on this matter.

Without adequate legal enforcement, workers all the more need representation. On December 7 and 8, China Labour Bulletin made several calls to two different levels of China’s official union to find out if the union had taken actions to represent Baoyi workers.

CLB first called the union specific to the Economic and Technological Development Zone in Yangzhou, at the same level of the Social Security Bureau we called. The union official denied that there was a strike at the Baoyi factory, stated that the office was busy, and hung up the phone.

Next, CLB called the Labour and Economic Work Department of the Yangzhou Municipal Federation of Trade Unions, a higher-level union. The staff who answered the phone claimed they were not aware of the strike, but agreed to forward CLB’s concerns and suggestions to the relevant departments within the union’s structure.

Although CLB researchers did not find any general records of an enterprise union at Baoyi, an enterprise union is referenced in several court judgements involving the Baoyi factory between 2014 and 2019. According to the legal documents, the enterprise union on several occasions approved Baoyi’s unilateral termination of labour contracts, including in a case where a worker was fired for calling for a strike on WeChat.

From these legal claims, CLB researchers have doubts that the enterprise union is fit to represent workers in their recent large-scale strike or in ongoing unpaid social security.

Baoyi’s Taiwanese parent company Pou Chen moves production to Indonesia

Baoyi is owned by Taiwan's Pou Chen Corporation and produces athletic shoes for Converse, a division of Nike. Nike is a member of the Fair Labor Association (FLA) and is therefore required to abide by the FLA's guidelines, which include that companies should comply with local laws.

Baoyi was established in 2006. The factory’s website states that it has 15 production lines and employs more than 3,200 workers. However, Open Supply Hub records indicate that 2,062 workers were employed as of March 2022, and workers posting about the November 2023 strike stated that about 1,000 workers were employed in late 2023.

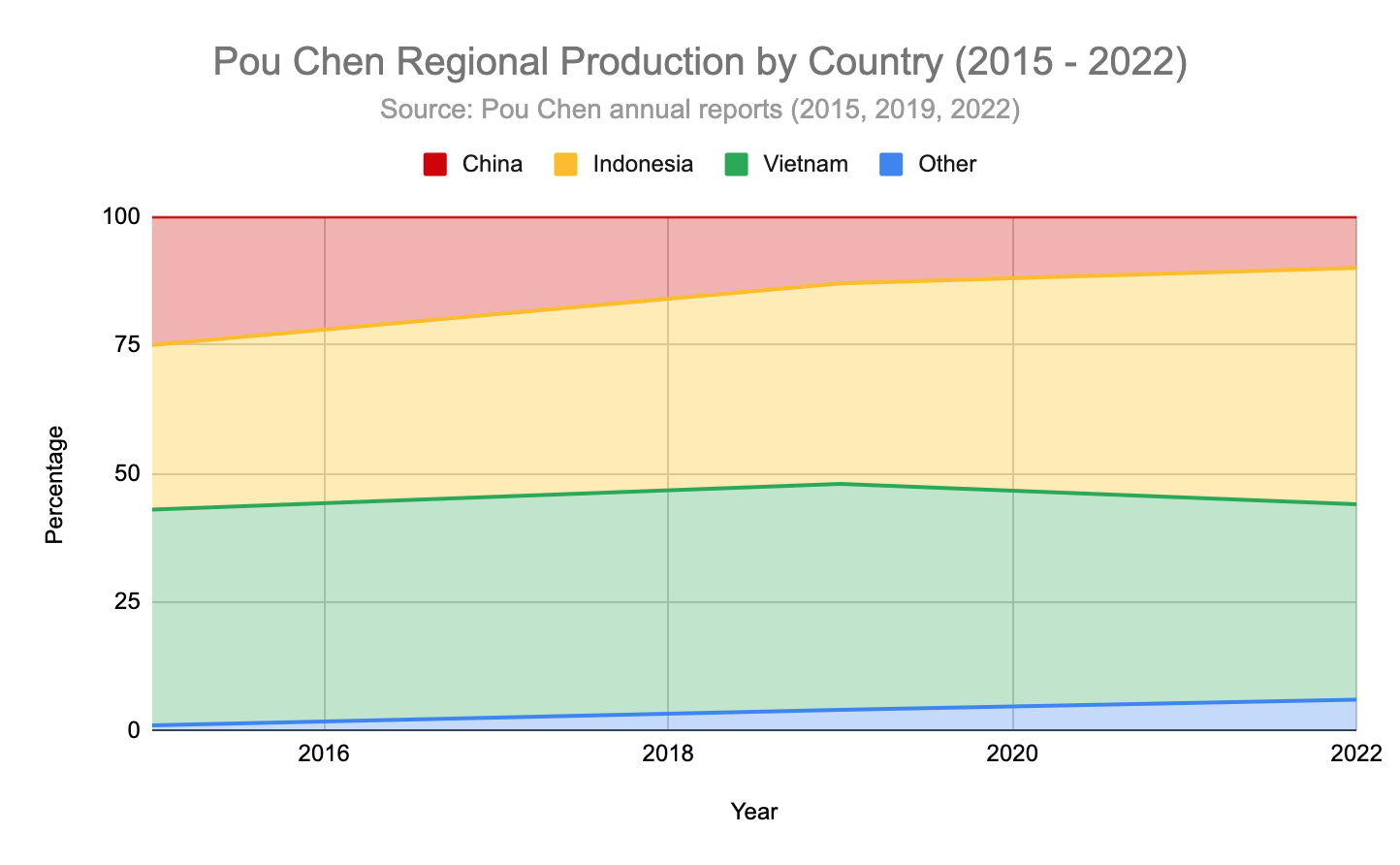

According to Pou Chen’s annual reports, in 2015, a quarter of Pou Chen’s production was in China. By 2019, only 13 percent was in China, and as of 2022 that has dropped to only 10 percent. Meanwhile, production in Indonesia rose from 32 percent to 46 percent in the same time period. The other approximately 40 percent has been in Vietnam.

The gates of a Pou Chen factory west of Jakarta. Source: CLB File Photo

Whether in China, Indonesia, Vietnam, or elsewhere, Nike and Pou Chen should ensure not only that domestic laws are followed by factories producing for them, but also that international standards on human rights and labour rights are followed. Specifically, workers in their supply chains must have access to the freedom of association and fair collective bargaining mechanisms, and they should be paid a decent wage for their work. In addition, workers must have the right to access information in a timely and transparent manner on matters that affect their livelihoods.

For Baoyi workers who are out of their jobs, Nike and Pou Chen should follow up to ensure they are in fact paid their legal economic compensation according to the Labour Contract Law and that their social security and housing provident funds are paid in full. Further, suppliers and brands should have responsible disengagement strategies, particularly as global supply chains are undergoing widespread change these past several years in Asia.

Further CLB reading: